Photo: Grapple nuclear test, Malden Island, Kiribati, 1957.

Between 1957 and 1962, the UK and USA undertook 33 atmospheric (above ground) nuclear tests at Malden and Kiritimati (Christmas) Islands, now part of the Republic of Kiribati.

The health of the Kiribati populations – and the military personnel from Fiji, UK, New Zealand and the USA who participated in the nuclear tests – has been severely impacted by the radioactive fall-out from these tests.

In 1959, Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh (husband of Queen Elizabeth II) visited Christmas Island on his Pacific Tour. He was warned not to drink the water due to potential contamination from the nuclear tests. But for the 43,000 military and scientific people participating in the nuclear testing program, and for the people living in the region, not drinking water is not an option. Indeed, the radioactive contamination was not just in the water. It rained down on them from the sky after each nuclear test, and contaminated the lands, buildings, wildlife and food.

This radioactive contamination has caused severe health impacts on the health of the Kiribati populations, the military personnel who participated in the nuclear tests, and their offspring. However, the governments involved in the nuclear tests have not recognized these impacts and have been derelict in their duty to provide support for those affected.

The UK, for example, claims that ‘Almost all the British servicemen involved in the UK nuclear tests received little or no additional radiation as a result of participation.’ However, this claim has no scientific or evidential basis, especially as ‘radiation exposures for service personnel … were not systematically monitored, and personal protection was minimal.’ (2015 Report of the International Review of the Red Cross). Indeed, a number of military personnel involved in the tests believe that they, and the indigenous populations, were used as ‘guinea pigs’ to see the impact of radiation on people. They point to UK military memos that show the UK wanted to understand the ‘effects of nuclear explosions on personnel and equipment.’

Until now, the indigenous populations, the military personnel involved in the tests and their affected offspring, have been mostly forgotten or ignored.

A new report from Pace University’s International Disarmament Institute expresses hope that increased attention to those affected by the tests is possible in light of the Victim assistance and environmental remediation obligations in the new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

The report documents the humanitarian, human rights and environmental harm caused by the nuclear weapons tests, explores the TPNW obligations and makes recommendations on actions to be taken to implement these obligations with respect to the impact of the UK and USA nuclear tests in Kiribati.

The experience of Kiribati is not unique in the Pacific. The UK, USA and France conducted over 300 nuclear detonations in the Pacific region – in Australia, Marshall Islands, Johnston Atoll and Te Ao Maohi (French Polynesia).

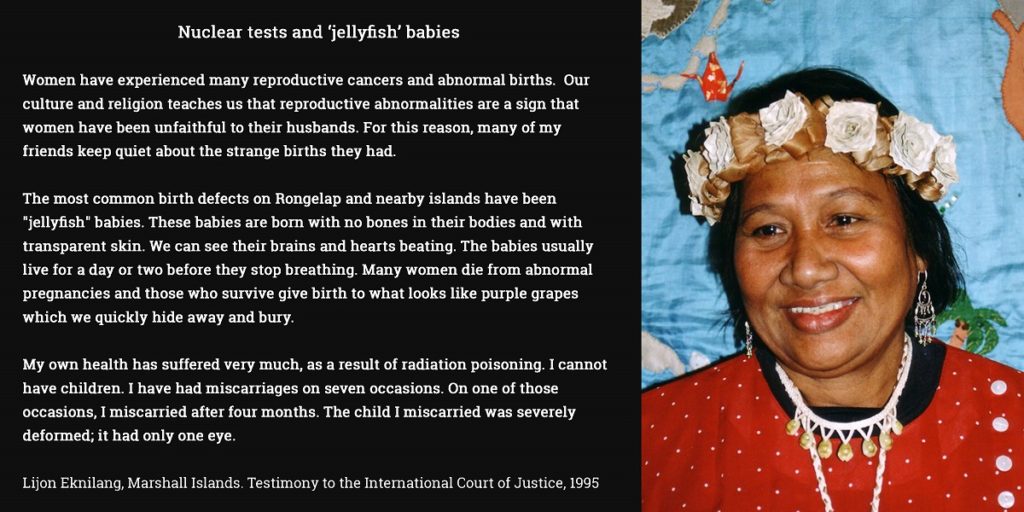

Testimony by the Marshall Is to the International Court of Justice about the impact of nuclear tests in the Pacific was instrumental in moving the Court to conclude in 1996 that ‘The destructive impact of nuclear weapons cannot be contained in either space or time.’

In 1997, Abolition 2000 held a conference in Moorea, French Polynesia bringing international nuclear abolition campaigners together with Pacific peoples impacted by the nuclear tests, in order to build awareness, cooperation and campaigns on the issue.

At that conference Abolition 2000 adopted the Moorea Declaration which highlights the particular suffering of indigenous and colonised peoples in the Pacific and in other regions as a result of the production and testing of nuclear weapons. The declaration also calls for governmental and nongovernmental action to redress the environmental degradation and human suffering that is the legacy of the atomic era.

The Moorea Declaration has stimulated and guided action by Abolition 2000 members and affiliated networks (such as ICAN), including to highlight the impacts of nuclear tests in the series of international conferences on humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, and to successfully advocate for the inclusion of victim assistance and environmental remediation in the TPNW.

As countries ratify the treaty, civil society campaigners have a new opportunity to move the States Parties to give assistance to those populations impacted by the nuclear tests. There is also a new opportunity to increase the pressure on the governments who undertook the tests (most of whom are unlikely to become parties to the TPNW) to uphold their obligations to provide adequate victim assistance and environmental remediation.

There have also been a number of developments in international environmental and human rights law, and in law protecting future generations, that can be used by civil society to put additional legal pressure on governments to act, regardless of whether or not they join the TPNW. This law has been the subject of a number of recent conferences, appeals and reports. See, for example the Basel Conference and Declaration on trans-generational crimes of nuclear weapons & nuclear energy (Sep2017) and Nuclear threats, climate change: We’re obligated to protect future generations, The Hill (USA), January 2018.

And there could be further opportunities to highlight these issues and build international awareness through the upcoming UN High-Level Conference on Nuclear Disarmament.